1. Paul’s Ministry and Timothy’s Calling

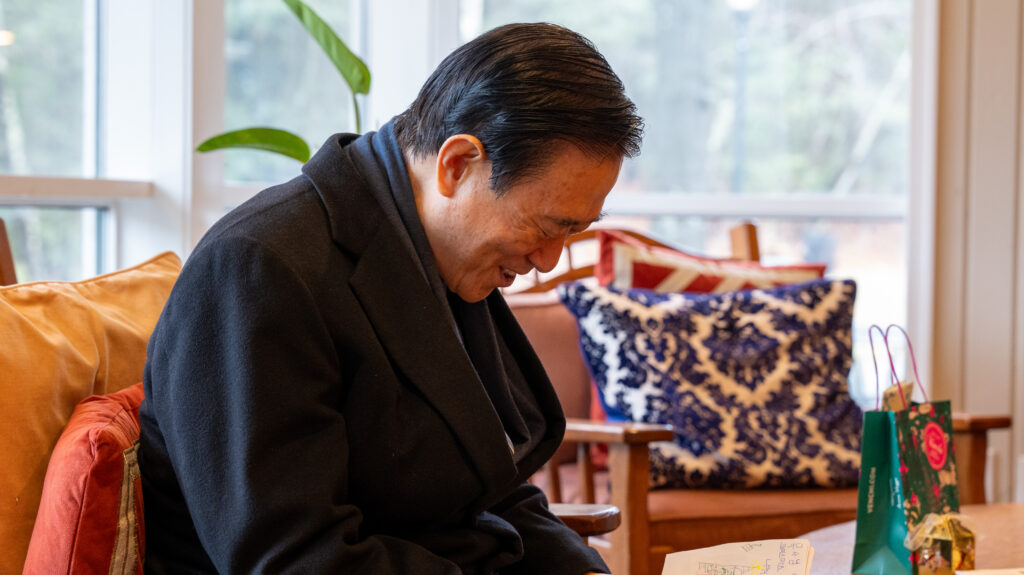

Pastor David Jang examined what mission the Lord entrusted to us in the scene where He appeared to His disciples after His resurrection. John 21 can be divided into three main sections. The first section deals with missions, the second with shepherding, and the third with “time,” that is, the end times. Following these three themes, we can see the profound exhortations the Lord Himself left with His disciples. The core of these exhortations is to fulfill the calling entrusted to each of us without confusion. Even after His resurrection, the Lord once again made clear to the disciples who He was and what they had been called to do. That same calling applies to us today. In other words, as believers in the resurrected Lord, we must carry out our clear mission and responsibility in the context of missions, shepherding, and the anticipation of the end times.

Following this message, the church finished studying First and Second Thessalonians. These letters to the beautiful Thessalonian church contain profound teachings and warnings about eschatology, along with practical pastoral advice. This is valuable instruction for our church today as well. Next, in Paul’s epistles, we come to the so-called “Pastoral Epistles”—First and Second Timothy, and Titus. Pastor David Jang emphasized the importance of paying attention to this section. The Pastoral Epistles are letters in which Paul provides pastoral guidance to his disciples in ministry, Timothy and Titus. These documents provide specific teachings on church administration, the attitude of shepherding, methods of caring for believers, and church order.

Pastor David Jang also gave a brief account of how pastoral theology has developed over the course of church history. The Catholic Church (the old church) experienced the Reformation, giving birth to the Reformed churches, i.e., Protestantism, with key reformers such as Martin Luther, John Calvin, and Ulrich Zwingli. Afterward, Protestant Orthodoxy emerged, which in turn faced backlash with the rise of Liberal Theology. However, when Liberal Theology began to threaten and undermine the church seriously, a movement called Neo-Orthodoxy arose to return once more to Protestant Orthodoxy. Leading figures such as Karl Barth, author of Church Dogmatics, Paul Tillich, Emil Brunner, and Reinhold Niebuhr strove to defend the gospel, with Karl Barth residing in Basel, Switzerland.

Eduard Thurneysen (1888–1974), a Swiss theologian from Basel, had a significant impact in establishing pastoral theology for that era. He studied at the University of Basel and later taught at the University of Berlin. His major work, Pastoral Care, offers specific guidance on how to conduct pastoral ministry in real-life settings. Pastor David Jang recalled that in his younger years, he was deeply immersed in Thurneysen’s writings and that when he visited Europe, he always wanted to visit Basel.

Pastoral theology falls under the broader discipline of Practical Theology within the study of theology. Typically, in theological education, students learn foundational subjects in the first year, biblical theology and church history (historical theology) in the second year, systematic theology (doctrine) in the third year, and practical theology in the fourth year. Homiletics (preaching) and pastoral theology fall under practical theology. The root and basis of practical theology is Scripture. Among biblical texts, Paul’s Pastoral Epistles (First and Second Timothy, Titus) contain the core principles and framework for church ministry. Hence, for those entrusted with caring for the body of Christ, these Pastoral Epistles serve as vital guides.

Following the Pastoral Epistles comes Philemon, which, though addressed to a single individual (Philemon), contains important truths meant to be read by the entire community. Then, after the thirteen Pauline Epistles (Romans through Philemon) comes the Book of Hebrews. Hebrews has long been a subject of debate because its author is not clearly identified. Its format differs from Paul’s epistles, and it lacks Paul’s customary greetings at the beginning and end. However, Hebrews 13:23 says, “You should know that our brother Timothy has been released, with whom I shall see you if he comes soon.” Because Paul so often highlighted his close relationship with Timothy, some scholars have suggested that Hebrews may be Paul’s work.

One of Paul’s beloved co-workers was Timothy, whose name appears frequently throughout Paul’s letters. Among Paul’s pastoral team, Timothy and Titus stand out as those who actually took on pastoral leadership. Of course, there must have been many unnamed servants who devoted themselves without seeking recognition. Even by looking at Romans 16, we see numerous co-laborers of Paul mentioned. Paul valued team ministry, fulfilling the mission of both evangelism and shepherding together with his many co-workers. Among them, Timothy held a particularly special role, appearing as a co-author in no fewer than six of Paul’s letters (2 Corinthians, Philippians, Colossians, 1 & 2 Thessalonians, Philemon).

When we look more closely at who Timothy was, we learn that Paul took him on as a co-worker during his second missionary journey when revisiting the region of Derbe and Lystra (Acts 16:1–3). His mother was a believing Jew, his father was a Greek, and his grandmother Lois was also a woman of sincere faith, as Paul notes in Second Timothy. Timothy was known for his gentle character, yet he was also anxious under difficult circumstances. The church faced false teachers internally and external persecution, so much so that Timothy suffered from stomach troubles (1 Timothy 5:23). According to 2 Timothy 1:4, “recalling your tears,” he was someone who shed many tears.

During the first missionary journey, Paul set out from Antioch with Barnabas and Mark, traveling through various regions to proclaim the gospel. In Lystra, he healed a man lame from birth, and the locals attempted to deify Paul and Barnabas. Paul firmly corrected their error and kept preaching, which incited some jealous Jews to stone Paul, leaving him for dead. However, God “raised him up” (Acts 14:19–20). The name “Lystra” means “a flock of sheep,” yet it was a place where Paul suffered greatly and then experienced a miraculous recovery. On the second missionary journey, when Paul returned to that land, he met Timothy, whose name means “one who fears God.” Though Lystra was a place stained with Paul’s blood and tears, it was there that God introduced Timothy, a precious co-laborer.

First Timothy is believed to have been written around AD 63–65, after Paul’s two-year house arrest in Rome when he was briefly released. After his release, Paul embarked on further travels, leaving Titus on the island of Crete and Timothy in Ephesus. The Ephesian church was a major congregation where Paul had invested three years of intense pastoral work. It was a church that experienced significant revival, making it all the more crucial to safeguard. Meanwhile, Paul was eager to go even to Spain (Rom. 15:28) and pressed on to other mission fields. However, false teachers had infiltrated the Ephesian church and were causing confusion, so Timothy had to stay and straighten things out.

Reading through the opening of First Timothy, Pastor David Jang explained in detail the meaning and background of the letter Paul wrote to Timothy:

“Paul, an apostle of Christ Jesus by the command of God our Savior and of Christ Jesus our hope” (1 Tim. 1:1).

Here, the word “Savior” is sōtēr (σωτήρ, sōtēros in the genitive form) in Greek. This was a title customarily given to the Roman Emperor at that time, but Paul uses it for God, declaring that it is God, not the emperor, who is the true Savior of the world. Furthermore, Christ Jesus is “our hope” for both Paul and Timothy:

“To Timothy, my true child in the faith: Grace, mercy, and peace from God the Father and Christ Jesus our Lord.” (1 Tim. 1:2)

Paul refers to Timothy as his “true child in the faith,” emphasizing Timothy’s special place in his life. Also, whereas Paul frequently opens his letters wishing “grace and peace,” here in First and Second Timothy he adds “mercy” as well. In chapter 1, Paul deeply reflects on God’s mercy shown to him, a sinner.

Paul states that he left Timothy in Ephesus “so that you may charge certain persons not to teach any different doctrine” (1 Tim. 1:3). Certain people in the Ephesian church were devoting themselves to “myths and endless genealogies” (1 Tim. 1:4). These individuals, relying on the Old Testament and various traditions, exaggerated or misinterpreted myths and genealogies, diverging from the fulfillment of the gospel in Christ. Also, influenced by Gnosticism, some were causing arguments and disputes within the church.

A pastor has the responsibility to protect the church from “different doctrines.” Even in this age, various foreign ideologies—such as secularism—attempt to infiltrate the church and distort the essence of the gospel. Therefore, pastors, as those entrusted with the care of God’s people, must hold firmly to the gospel and faithfully teach its core truths. This is a fundamental pastoral calling.

Paul points out that those who indulge in myths, genealogies, and contentious discourse have fallen into “vain discussion” (1 Tim. 1:6–7). He explains that, although the law itself is good (1 Tim. 1:8), its role is to make sin known and point people to the gospel (1 Tim. 1:9–11). In other words, the law can condemn sinners but cannot save them; it is a guardian leading us to the gospel (cf. Gal. 3:24).

Paul then again refers to “the gospel of the glory of the blessed God” (1 Tim. 1:11) that he had received, and he expresses his gratitude for having been entrusted with this gospel:

“I thank him who has given me strength, Christ Jesus our Lord, because he judged me faithful, appointing me to his service” (1 Tim. 1:12).

Pastor David Jang emphasized this verse in particular. Paul regarded the responsibility of his calling not merely as a burden but as an occasion for gratitude. He considered it a joy and a privilege that someone so undeserving—who was not even worthy of salvation—had been chosen for this immense task of “pastoral” ministry.

Continuing, Paul confesses,

“though formerly I was a blasphemer, persecutor, and insolent opponent. But I received mercy…” (1 Tim. 1:13).

He discloses how he once opposed Jesus Christ and took the lead in destroying the church. Recognizing that he, sinful and weak, received mercy, he can say, “Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners, of whom I am the foremost” (1 Tim. 1:15). This humble admission resonates powerfully with both pastors and believers.

Quoting this verse, Pastor David Jang insisted that “all pastoral ministry begins with the recognition that we are sinners.” A pastor who does not truly grasp that they themselves have been forgiven and shown mercy cannot lovingly serve the church community. Like the expression “wounded healer,” only those who know what it is to be forgiven and to weep in repentance can embrace and care for the sins and wounds of others.

Paul continues,

“But I received mercy for this reason, that in me, as the foremost, Jesus Christ might display his perfect patience as an example to those who were to believe in him for eternal life” (1 Tim. 1:16).

Paul believes he, the worst of sinners, was shown mercy to serve as a model for all who would later believe and receive eternal life. In other words, the gospel’s power is proven by the fact that it not only saves the unworthy and broken but also uses them.

Pastor David Jang underscored how practical and crucial this exhortation is for real-life ministry: “wage the good warfare” (1 Tim. 1:18). In actual pastoral settings, this can be both painful and beautiful. You must guard the church from “different doctrines,” preserve the gospel’s essence, care for believers in love, and work in teams with fellow workers who share in weeping and rejoicing. Sometimes, though, there are those whose “faith is shipwrecked” (1 Tim. 1:19–20), and you must bear that pain. Such is the reality of ministry.

Paul concludes the chapter by giving “honor and glory” to “the King of the ages, immortal, invisible, the only God” (1 Tim. 1:17). Pastor David Jang stated that this is the ultimate goal of both ministry and faith. Ultimately, our life and service aim to glorify God, and that glory is possible not because of who we are, but because of the Lord’s mercy and grace.

2. Ministry Built on Mercy

Pastor David Jang then highlighted “ministry” as the overarching theme of First Timothy, and specifically the “mercy” that underpins it. In chapter 1, Paul first explains why the church must be guarded, i.e., how dangerous false teachings can be. In the end, he concludes that the driving force of ministry is the mercy of God. Recalling that he was the foremost sinner who received mercy, Paul teaches that a pastor must remember and testify to the mercy they have received, thereby caring for the congregation.

Pastor David Jang stressed that this is the power that brings forth “love.” First Timothy 1:5 declares, “The aim of our charge is love that issues from a pure heart and a good conscience and a sincere faith.” The ultimate purpose of all teaching and warning in the church is none other than “love.” And love flows naturally when we deeply realize the great mercy we have received from the Lord. This is the essence of shepherding.

A pastor must pay close attention to everything that happens inside and outside the church. This includes worldly influences that disrupt the church, false teachers within who promote erroneous doctrines, pointless debates, and even the weariness of unnamed servants who sacrifice themselves for the church. Addressing all of these requires humility and tears. As Acts 20:17–19 shows, when Paul took leave of the Ephesian elders, he said he served the Lord “with all humility and with tears.” Likewise, Pastor David Jang repeatedly said, “Pastoral ministry is tears.” Timothy, who was timid, tearful, and even suffered from stomach problems, was precisely the one God chose to place in the pastoral field—an example of how God uses “what is weak to shame the strong” (1 Cor. 1:27).

Additionally, Pastor David Jang mentioned that ministry must be carried out in teams. Beyond Timothy and Titus, Paul had many co-laborers: Silas, Luke, Aquila and Priscilla, Epaphras, and many more who were all dedicated to preaching the gospel and building up church communities. A church must never become a one-man show. Its great strength lies in weeping together, rejoicing together, and bearing one another’s burdens.

He also emphasized that evangelism (missions) and shepherding (pastoral care) are inseparable. When the risen Lord directly gave His disciples their commission, He gave them the Great Commission: “You will be my witnesses to the end of the earth” (Acts 1:8). At the same time, He also said, “Feed my lambs” (John 21:15). During his first, second, and third missionary journeys, Paul constantly revisited the churches he had planted or established, sending letters to ensure they were thriving. Whenever the gospel is preached, it reaches people; nurturing these people and guiding them is the heart of shepherding.

Shepherding is love. Without love, there can be no true shepherding. According to First Timothy 1:5, this love “issues from a pure heart and a good conscience and a sincere faith.” On the other hand, the love found in Scripture is not simply a result of our striving or hard work; it originates in grasping how God first showed mercy to us, though we were sinners. That is why Paul keeps recalling, “I am the foremost” of sinners. Because he continually remembered who he had been, and the unfathomable grace of God, he was able to preach the gospel fervently while simultaneously grieving over any possibility that a church might scatter or collapse.

It is for this reason that First and Second Timothy and Titus, among Paul’s letters, are so important, for they offer specific pastoral directives and insight into Paul’s pastoral philosophy. Reading First and Second Timothy and Titus, we learn about the qualifications for church leadership, how to interact with congregants, the priority of worship and prayer, how to respond to false teachers, and the order of the church. These are foundational truths that guide how modern pastors—like Pastor David Jang—should conduct ministry.

Tying these points back to First Timothy 1, Pastor David Jang noted that even when a church is shaken, the phrase “I remember your tears” (2 Tim. 1:4) suggests that a pastor’s tears are not a sign of weakness, but rather a holy offering to protect the congregation. Paul earnestly hoped Timothy would never give up. He reminded him that both he (Paul) and Timothy had received mercy, and in that remembrance, they would encourage one another.

The most fundamental driving force in ministry is grace and mercy. Those who have received grace and mercy become thankful stewards of God’s church. That is why Paul says, “He judged me faithful, appointing me to his service” (1 Tim. 1:12). A pastoral or ministerial office is not some position you seize through achievement or merit. When you receive a post in the church, whether you treat it as an honor and privilege, or merely a burden, will determine your fundamental attitude toward ministry. Paul, once a fierce persecutor of the church, was appointed by God’s mercy to be a preacher of the gospel. That fact alone made him grateful every day, and that gratitude became the source of his ministry.

Thus, even when encountering individuals who harbor hostility toward the church or who disrupt it, pastors must attempt correction. If that fails, they must take firm measures to preserve the church’s holiness. In First Timothy 1:19–20, Paul mentions Hymenaeus and Alexander as examples of those who made “shipwreck of their faith.” Paul says, “I have handed them over to Satan that they may learn not to blaspheme.” Though he likely tried to embrace them in love, they persisted in attacking the church and distorting the gospel, leaving no choice but expulsion. Such resolve is also needed in real ministry.

In short, pastoral ministry is not easy. In countless sermons and lectures, Pastor David Jang has repeatedly said, “Pastoral ministry is the precious work of tending the body of Christ, yet it cannot be done without tears.” We can glimpse the reality of ministry in the relationship between Paul and Timothy and between Paul and Titus. Teaching that lacks a foundation of love eventually leads to divisions and conflict. But when teaching is rooted in love, sustained by grace and mercy, it revitalizes souls and strengthens the community.

Today, the church faces numerous challenges. Secularism, pluralism, materialism, and humanism all attempt to dilute the truth of the gospel. Within the church, theological errors and selfish ambitions also arise, causing divisions among believers, compounded by the post-COVID slump. Now more than ever, we should seek wisdom from these instructions Paul gave Timothy 2,000 years ago. Ultimately, everything hinges on the love that springs from God’s grace and mercy. We must not abandon “the good fight of faith” (1 Tim. 1:18).

After His resurrection, the Lord said in John 21, “Feed my lambs,” and in Acts 1:8, “You will be my witnesses to the end of the earth.” These two commands cannot be separated, and many co-workers—like the Apostle Paul and his team—poured out tears and dedication as they engaged in both missions and pastoral care. Those who have been entrusted with the church must remember that they themselves have received mercy, love the flock, and carry the gospel to the ends of the earth.

Pastor David Jang has continued to exhort pastors and congregations worldwide, including in Korea, to maintain a biblical foundation and a correct attitude toward these two tasks (missions and shepherding). Every time we open First Timothy, we should give glory to God our Savior and remember with gratitude the “mercy” that came to us, the foremost of sinners. That gratitude should free us from meaningless debates, genealogies, and hollow words, enabling us to build up the church, resolve confusion, and guide people to life through genuine love.

First Timothy 1 shows Paul telling Timothy, “Guard the church, defend the gospel, and never forget that you, too, were once the foremost sinner who received mercy.” Paul’s vision of ministry is not adorned with lofty rhetoric. It is not preoccupied with myths or genealogies or complex reasoning. At its heart lies the love that springs from the Lord’s grace and mercy. Therefore, modern church leaders and believers must constantly revisit the basics of ministry and strive to make the church community a place of love and grace rather than contention and argument.

The reason this task is not easy is that even a major church like Ephesus faltered, and today’s churches face no fewer difficulties. Yet just as Paul was able to rise again, just as Timothy endured despite his frailties, so will those who cling to God’s love and mercy find the strength to persevere. With that strength, we can establish our churches firmly and, in obedience to the command of our Savior God and our hope Christ Jesus, take the gospel to the ends of the earth. This, according to Pastor David Jang, is the true substance of “the proper posture toward ministry, missions, and the end times.”

Hence, we see that John 21 and Paul’s counsel to Timothy form a continuous thread. The commission of the risen Lord and Paul’s exhortation to uphold the church both serve as foundational pillars of pastoral theology. The church must lovingly care for the flock, guard itself from deceptive doctrines, and prepare for the Lord’s return. Throughout all of this, as Pastor David Jang’s messages repeatedly affirm, we must remain rooted in “the mercy of God.” The mercy that saved us from our sins is the eternal power that sustains both evangelism and pastoral care.